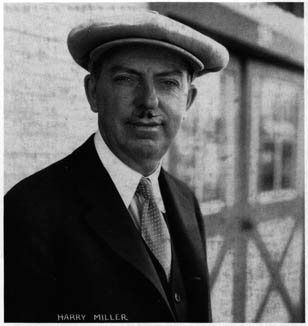

"Harry Miller was, quite simply, the greatest

creative figure in the history of the American racing car.

His engines dominated American oval-track

racing for almost half a century. Most of the speed records which there were

to be had on land and water were held at one time or another by those engines.

He created the school of American thoroughbred engine design, which was faithfully

followed by those who sought to outdo him. He was the originator, in the

United States, of the racing car as an art object. He had a passion for metalwork

and machinery that soared above and beyond all practical consideration. Parts

of his machines that never would be seen by eyes other than those of the

builders were formed and finished with loving care. His dedication to artistic

and noble workmanship drew to his organization other technicians who believed

in these same values. A whole sub-culture spread from the Miller nucleus,

to become a permanent and integral part of innovative, artistic Southern

California culture as a whole. It spilled over into the aircraft industry

and it shook the automotive industry worldwide.

Miller created the first really streamlined

closed car in the United States, and one of the first in the world. That

was in 1917, and he was already telling journalists about using airfoil sections

for improving the traction of super-light cars. He created unsupercharged

engines of fantastic efficiency. Then he became the master of supercharging,

achieving far more fantastic results, making the world passenger-car industry

look archaic. He gave the world front-wheel-drive as a practical reality.

He created really tractable and practical four-wheel drive racing cars in

the early Thirties, decades before almost anyone could appreciate the value

of the principle. He always lived in the future, up to the time of his death

in 1943.

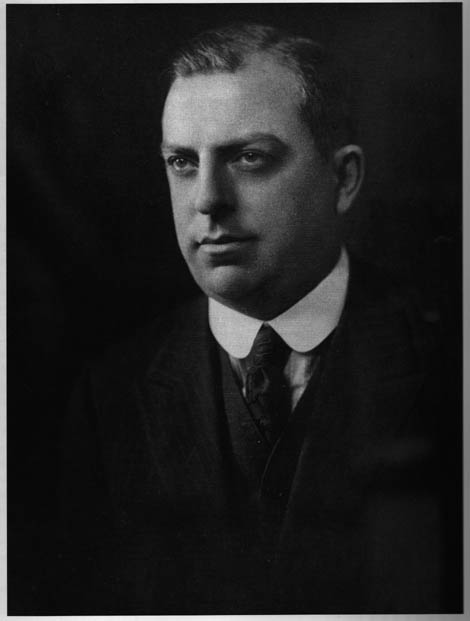

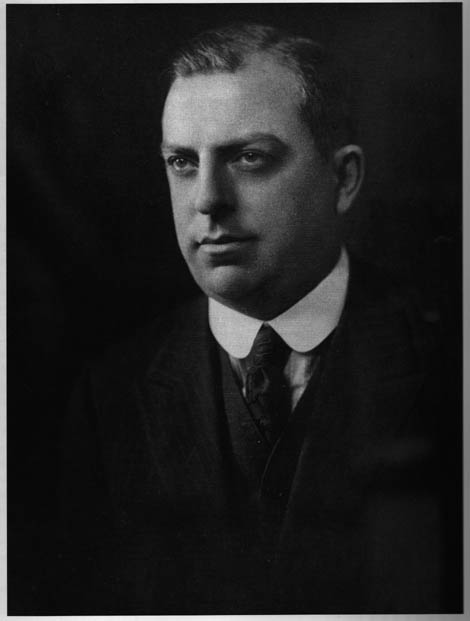

He stood about 5 ft. 6 in., had blue eyes,

black hair, fair complexion, ruddy cheeks, and red lips. He was shy, silent,

and reflective. He was in the habit of lying awake at night, while his brain

worked. He did not waste much time on sleep. He had little to say, unless

the topic should be machinery or, preferably, engines, in which case he

could go on forever, with an interlocutor on his intellectual wavelength.

"He was a funny man," his wife said, meaning

that he was clairvoyant. "Someone's telling me what to do," he told intelligently

sensitive Leo Goossen. "I have a control, and I count on it."

Period 1875-1916

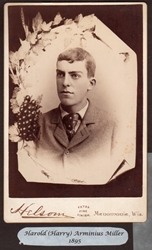

Harry Miller was born in Menomonie, Wisconsin,

on December 9, 1875. In 1894 he moved to Los Angeles. During the early 1900s,

Miller had been developing an original design for an improved carburetor.

With the aid of a used lathe and drill press and a few essential tools, he

began production. He filed for a patent to protect his carburetor design in

1909 and received it that December, five days after his 34th birthday. His

business career took off with a rush.

In 1912, Miller's carburetor company and

assets were purchased by the sons of Charles Fairbanks and moved to Indianapolis

in April. Miller continued to invent and file patents and in 1913, he incorporated

the Master Carburetor Company, for the manufacture and sale of a new and

very different carburetor. With brush-fire rapidity, the Master came overwhelmingly

to dominate racing in the West, and then spread all the way to the Atlantic

Coast. It was a resounding commercial success in the passenger-car, aeronautical,

and marine fields.

Early in 1912, Miller had developed

- with carburetors bodies in mind - an original blend of aluminum, nickel,

and copper, which he called Alloyanum. Continuing his experiments, Miller

found that his new alloy was good for much more than light, strong carburetor

bodies. He found that it made marvelous pistons and by in late 1913 he began

pioneering their sale. His pistons swiftly became a virtual necessity for

high-performance and aero engines. And, in spite of the Master sale, he

continued to design and fabricate special carburetors and inlet manifolds

for high power output. These factors, plus a fine machine shop that could

duplicate the most exotic parts, served to make the roomy plant of the Harry

A. Miller Manufacturing Co. the west coast mecca for anyone and everyone

in the country with an interest in optimum performance on land, water, or

in the air. By 1915, at age 40, Miller had made it.

The first original Miller engine was commissioned

in 1915. It was an inline 6, single-overhead-cam aircraft engine designed

in the current aero Mercedes manner. An engine followed for "Wild Bob" Burman

whose connecting rod broke in his 1913 Grand Prix Peugeot. Aside from a

few bits, which could be recuperated from the scattered Peugeot, an entirely

new engine and chassis was constructed.

Pleased with the result, Bob ordered a totally

new car with a new engine, a combination he never saw finished as a result

of his horrific fatal accident at Corona in 1916. The second Burman engine

was a very different engine design from any other twin-cam engine of the

time - it incorporated a totally enclosed valve gear, predating Ballot by

three years.

Period 1917-1920

Miller followed these engines with a series

of 289-ci single-overhead camshaft 16-valve fours constructed of Alloyanum

extensively. The engines employed wet steel liners - the world's first, at

least among racing engines. One of these engines was placed in what remains

to this day as one of the most dramatic racing cars of all time: the Miller

Golden Submarine. Designed and built in 1917, the entirely enclosed and

aerodynamic racecar was sensational wherever it went. On a sister car, Miller

fitted hydraulic front brakes for 1919, making it the first known appearance

of such brakes on a racing car.

Miller's last car of the decade was the

TNT car with a 183-ci four. It was the world's first twin-cam engine to use

light-alloy construction along with wet cylinder liners. Its patent shows

flat-spoke wheels, five years ahead of Bugatti; four-wheel brakes and lightened

brake drums; the engine as a stressed chassis member; and the profile of

what would become the classic shape of American oval track racecar bodies

for at least a couple of decades to come.

Period 1920-1923

1920 opened the decade in which Miller would

become the supreme American racecar constructor. In order to exert the most

rigid control over the balance between the strength and the lightness of

parts, Miller broke with the established practice of adapting production-car

components to racecar use. Practically every part of every Miller car was

always made in his own plant. For every part, an engineering drawing existed.

The importance of esthetic effect was of fundamental importance. It took

about 6,000 to 6,500 man-hours to build a complete car. Between 700 and 1000

hours went into beautifying - just putting the finish on each machine.

In 1921, incorporating the best of the world's

racing engine designs along with his own innovations, Miller designed and

produced the 183-ci engine. A twin-cam, four-valve, straight- eight, it eventually

produced 185 bhp at 4400 rpm. As soon as the engine was sorted out, Miller

began constructing complete racing cars in which to mount the engine. About

a dozen 183s were built before the 122-ci formula was enacted in 1923.

From the beginning, Miller tested carburetors

with two, four, or eight throats. Miller and his team experimented with ram

tuning of induction systems, using a stopwatch and cut-and-try methods at

the Beverly Hills board track. The result was beautiful ram-tuned intake runners

and carburetor throats for each individual cylinder.

A Miller 183 driven by Tommy Milton won

the 1921 national championship - Miller racecars won every annual national

championship thereafter. By mid-1922, the Miller 183 had become the hottest

thing on wheels. It was in March that Jimmy Murphy placed an order with Miller

for a 183 to be installed in the Duesenberg racecar with which he had won

the French Grand Prix at Le Mans the previous July. Murphy won with that

combination at Indy in 1922 - and with that victory, Miller became a figure

of international importance. From this breakthrough, Miller almost overwhelmingly

reigned at Indy through the 1920s. Millers won five 500s and never placed

less than six cars in the top ten.

Period 1923-1925

In the summer of 1922, Miller began the

design of a new engine and car for the 122-ci class. The new engine was only

slightly changed: primarily the adoption of a two-valve hemispheric head

and a five-main-bearing crankshaft. The bodies of the 183s had been remarkably

narrow and lightweight, but those of the 122s seemed to be more so, the drawings

calling for a maximum width of 18 in and a total weight of 1350 lbs. Aerodynamically,

they were slippery projectiles, as the record list confirmed.

The Miller 122 was the first pure racing

car to be series produced and about fifteen cars were completed. Three cars

were built for European Grand Prix use, driven by Zborowski, De Alzaga,

and Murphy. In 1923, 46% of the Indy starting field was Millers; by 1925

it was 73%.

Early specimens of the Miller 122s developed

around 120 bhp at 5000 rpm. In response to the Duesenberg supercharging innovation,

Miller designed a centrifugal supercharger for the 122. It raised the output

to 235 bhp at 5800 rpm.

In 1924, a Miller 183 chassis set two international

speed records: 151.26 mph with a 183-ci engine and 141.17 mph with a 122-ci

engine. Many records continued to be established by the 122s in ensuing years.

As a result of a request for something uniquely

superior to anything in the world, Miller designed and produced the 122 front-drive

racing car in late 1924. Two were built before the 91-ci formula was enacted

in 1926. If Harry Miller had done nothing more in his highly creative career

than give the world front-wheel-drive as a practical reality, his significant

place in history would be assured.

The Miller front-wheel-drive car seemed

to be a perfectly integrated harmonious whole, as machine and sculptural

object. There was something about it that was close to being sublime. Without

the driveline through the cockpit, the driver sat some nine inches lower than

in the comparable rear-drive car. Miller further reduced the height of the

radiator and the result was a low, rakish car of unsurpassed beauty. The

long low hood of the new Millers bespoke nothing but power and established

a virtual mandate among stylists for a long hood, or the illusion thereof,

for decades to come. It was without doubt the greatest single milestone in

the development of the appearance of the automobile between the end of the

Edwardian era and the streamlining fad of the 1930s.

The Miller front-drive was a bombshell of

engineering and styling ideas tossed at a somnolent Detroit. There ensued

a frenzy of speculation and research into front-wheel drive, which eventually

abated after a few front-drive cars were placed into limited production.

Only racing cars, rather than passenger cars like the Cord L-29, demonstrated

the best possibilities of front-drive until the famous Citroen Traction-Avant

of 1934 proved its entire practicality and merit for the road.

Period 1926-1929

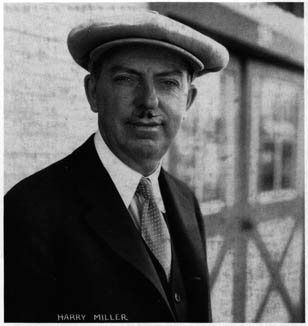

Harry Miller's fortunes remained steadily

ascendant throughout the Roaring Twenties. He made a great deal of money.

He had a comfortable house in town, a ranch in the Santa Monica Mountains,

and enjoyed the friendship of leading businessmen, sports figures, and Hollywood

stars.

In response to the new 91.5-ci formula,

Miller designed a new engine and racecar. The heart of these cars was a straight-eight

engine and body similar in outline and form to the 122. However, every single

component, except for proprietary parts, was designed and built anew just

for the 91. The Miller 91 rear-drive was built in series production and nine

cars were completed. Ten Miller 91 front-drives were built, each an individual

design.

Factory engines started out with an output

of 154 bhp at 7000 rpm. Intercooler innovations and internal refinements

by Frank Lockhart pushed the output to 285 bhp at 8000 rpm.

If you wanted to win, you had to buy Miller

- if you could afford it. A factory rear-drive cost $10,000 and a front-drive

cost $15,000. It was the price of admission: from 1926 to 1929, between 71%

and 85% of the Indy starting field were Millers.

In 1927, a Miller 91 rear-drive set an international

speed record of 164.84 mph, including a one-way speed of 171 mph, and an

international closed-course speed record of 147.729 mph. In 1930, a Miller

91 front-drive achieved 180.9 mph. Many other international speed records

were established.

As a result of Miller's car racing dominance,

boat owners approached Miller to produce powerplants for racing and sport

boats. Miller responded with marine versions of the 122-ci and 91-ci car

engines and with new designs of 310-ci straight-eights and 620-ci V16s. One

design in particular, that of a simple and reliable 151-ci four-cylinder,

was a popular seller and a constant winner.

Unfortunately, the looks, durability, and

quality of the Miller racecars, those qualities that made them so successful,

eventually led to their demise. A Miller chassis was the dream of every racer

and would-be racer in the country for dirt track use or, later, for widening

to use as a two-man Indy car. Eventually, every rear-drive 91 and all but

two 122s were re-engined and otherwise altered so greatly that their original

identity was lost.

Period 1930-1933

Just weeks before the crash of 1929, Harry

Miller took associates' advice and retired from his business. A $60,000 retainer

from Cord and the sale of his business for $150,000 allowed him a life of

luxurious comfort. But, at the age of 54, he was still a vigorous man, and

marvelous ideas kept coming to him. And so, in 1930, he set up a new engineering

business and soon hired back most of his old staff. However, the world had

changed from the Twenties: it was the Depression, there was little money

for racing and his wealthy patrons were gone. In three years he would be

bankrupt.

At the start of the decade, a prominent

racecar owner decided to try one of Miller's successful four-cylinder, 151-ci

marine engines in his racecar. It was successful beyond all expectations.

The prototype established a new international speed record of 144.895 mph.

Miller, asked to design a racecar version, developed an economy racing engine

to suit the hard times. A logical development of the well-tried marine engine,

it was the twin-cam, four-valve, 220-ci four.

Unfortunately, a throwback four-cylinder,

although clearly showing the path to a successful future, did not interest

Miller in the least. It hardly sold at all and, following his bankruptcy,

his company assets were sold at auction. It was Miller's long-time chief machinist,

Fred Offenhauser who picked up this engine design and continued to produce

and refine it - the design quickly became the indomitable Offy, the most

victorious racing engine of all time.

What entranced Miller was the idea of building

a super road machine to impress the titans of Detroit with whom he hobnobbed

at the Speedway. He was commissioned to design and build the finest and fastest

sports car yet seen in the United States - for the sum of $30,000. Of course,

the dream machine would be front-drive. A one-off 310-ci, twin-cam, supercharged,

V8 of 350 bhp was designed for it along with a new front-drive transaxle.

The hand-built car was completed in 1930.

While others would perpetuate certain of

Miller's concepts for decades to come, Miller was eternally in pursuit of

improved solutions to design problems. Unlike its highly specialized predecessors,

the 1931 series Miller racecar chassis was conceived as a sort of go-anywhere

racing machine. It was intended to perform outstandingly, whether skimming

over speedways or slogging it around the dirt tracks, which were totally

replacing the board tracks.

Only four cars were built: one with a 303-ci

V16 and three with 230-ci straight-eights. The cars performed well, winning

the national championship in 1932, winning at Indy in 1933, and repeatedly

placing in the top five in races around the country. Considering the very

small number built, the performance and racing record of these cars must

have been a source of pride to Harry Miller and his staff.

Those who knew him said that Harry Miller

was a man who would gamble his last dollar on the drawing board. Naturally,

the first worthwhile four-wheel-drive racing car design was his brainchild.

That he designed and constructed such a project in the gloomy fall of 1931

proves that he was in thrall to the passion of the machine, for the creditors

were swarming around.

Extrapolated from the front-wheel-drives

of the Twenties, and the four-wheel-drives had the same De Dion drive system

at both front and rear. A new 308-ci, twin-cam, V8 along with the complete

drive system was designed and two cars completed - at a cost of more than

$30,000. The cars raced unsuccessfully, due both to bad luck and design flaws,

at Indy and elsewhere in the early 30s, and the new cars had no opportunity

to demonstrate what they could do. In 1934, one of the cars was raced in

the Grand Prix of Tripoli and in the AVUS Grand Prix in Berlin. The other

car raced in hill climbs for a while before its retirement.

In the midst of building the four-wheel-drive

racecars, Miller also designed and produced his last road car, one of the

most incredible supercars of all time. It was a Roots-supercharged, twin-cam,

V16 of nearly 500 bhp, four-wheel-drive speedster - built at the remarkable

price of $35,000. However, without series production to work out the bugs,

it was a driving disaster - an ill-conceived car that looked better on paper

than at any later stage in its existence.

The failure image of four-wheel-drive became

deeply etched in the mass mentality and Miller was left to his rendezvous

with financial ruin. It is said that the four-wheel-drive cars were the cars

that clinched his imminent bankruptcy.

On July 8, 1933, the inevitable moment of

reckoning arrived: outside creditors filed suit and Miller was placed in

involuntary bankruptcy. He was wiped out - out of business, home, and ranch.

His world was smashed, but so were the worlds of loyal friends who had stood

by him through thick and thin and who had made it possible for him to become

supreme in his domain. Crushed by humiliation and guilt, Miller turned his

back on the region and culture that he had helped to build and that December

migrated east.

Period 1933-1943

Upon arrival in New York, his old crony,

Preston Tucker, sought Miller out. Tucker felt that a stock-block engine

in a modern, independently sprung chassis might have a chance to win. He knew

that Miller certainly could design such running gear, and that he, Tucker,

master salesman, had the chutzpah and contacts throughout Detroit to sell

the package to a major automobile manufacturer. It was to Edsel Ford that

Tucker grandly and eloquently pitched the idea. At the end of February 1935

a deal was struck for the construction of ten cars for the upcoming Indy

500, at a cost of $75,000. The machines and equipment to build the cars didn't

arrive until March, leaving less than sixty days to outfit the shop, complete

the design and drawings, build the avant-garde racecars, and test and develop

them.

The inevitable happened. The cars were rushed

together in an environment of unrelieved panic, twenty-four hours a day and

seven days a week. Only four cars qualified for the race and all retired

early for the same reason: a seized steering gearbox overheated by its proximity

to the exhaust. It could have been rendered perfectly operational if but

a few minutes of practice time had been available.

After the race and the fiasco, Henry Ford

himself ordered the ten cars hauled away, to be gotten out of sight for a

couple of years or so. The Miller-Ford dealt a devastating but passing blow

to the Ford image. Harry Miller was the fall guy for the unrealizable fantasies

of others, in which he had allowed himself to become enmeshed. What remained

were the most beautiful American racing cars of the decade. The harbinger

of a new age, they were low, rakish, streamlined beyond belief in every detail

except the elegant radiator grill.

After the Miller-Ford debacle, Miller formed

a business venture with the internationally renowned automotive stylist,

Tom Hibbard. Hibbard's vision was a trim speedster based on a shortened Ford

V-8 chassis; Miller's vision was a 91-ci straight-eight, mid-engined, fully

independently sprung sports car. Nothing came of either of their dreams.

Then, in early 1937, Miller's very first

client for a straight-eight engine reappeared in his life. Ira Vail commissioned

the design and construction of a pair of new four-cylinder machines to compete

against the old pre-World War I technology, which then reigned on the dirt

tracks and at Indianapolis. Miller's design of a lightweight aero engine,

deep chassis members, and independent suspension, included another truly

Miller first: disc brakes. Shortly after Miller began construction of these

cars, the Gulf Oil Company approached him and bought out the project. Justification

for the Gulf involvement in a racing car project was to furnish a test-bed

and showcase for the company's current gas and lubricants. The racecars

were completed but testing and attempts at qualifying revealed severe cooling

problems. They were disposed of and never raced again.

A program was launched immediately for the

design and construction of a team of much more ambitious, cost no-object,

racecars suitable for Grand Prix and Indianapolis competition. The aging,

unhealthy Miller took a deep breath and plunged into the last great effort

of his career. The car would be 180-ci six-cylinder, supercharged, four-wheel-drive,

mid-engined, independently sprung, disk braked technical tour de force. The

engine was the world's first to have oversquare bore/stroke dimensions. The

extremely complex car was rushed to completion and failed to qualify for

the 1938 Indy.

Miller radically redesigned the concept

and three new cars were completed for 1939. One crashed and burned dramatically,

one was withdrawn, and the other failed to complete the race. At the end

of summer, Miller's honeymoon with Gulf dissolved. He could never bring himself

to do things in the ways that large corporations required. Were Miller to

have played his cards right, he could have established a sinecure for himself

at Gulf in which to dabble on various projects during his declining years

while playing the role of elder statesman to the racing community. But,

of course, he was too independent and too beguiled by his own reputation

and constant luck to do so. There had always been an angel in the wings

to bankroll him in another venture.

Harry moved, by himself - his wife returned

to California - to Indianapolis where he engaged in various aircraft projects

involving Preston Tucker. All ended badly and a year later Miller moved to

Detroit. He set up a small business making test fixtures and tools and spent

the last two years of his life in near penury. At age 65, having suffered

from diabetes for years, and having acquired facial cancer, the end was

near. In early 1943 he suffered a heart attack and died on May 3. His ashes

were interred in Los Angeles with little fanfare, a sad passing for this

flawed but vital man."

![]()